I’m heading off next week to the Writers Police Academy, where I will be giving a talk on how to integrate research into your mystery writing…for TV and for books. In preparing my notes, I came across this old blog post about how I wrote the Diagnosis Murder books and episodes. It was great to read… because, after so long, it was as if I was reading something written by someone else. I think I gave some pretty good advice … so I’m sharing the piece again in case you missed it the first time or in the many magazines and books in which it has been excerpted or reprinted over the years.

I’m heading off next week to the Writers Police Academy, where I will be giving a talk on how to integrate research into your mystery writing…for TV and for books. In preparing my notes, I came across this old blog post about how I wrote the Diagnosis Murder books and episodes. It was great to read… because, after so long, it was as if I was reading something written by someone else. I think I gave some pretty good advice … so I’m sharing the piece again in case you missed it the first time or in the many magazines and books in which it has been excerpted or reprinted over the years.

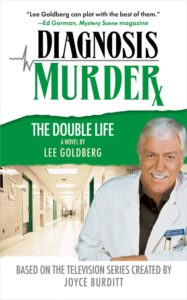

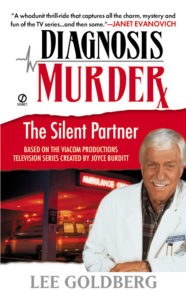

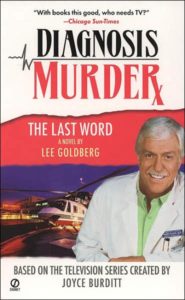

I’ve just signed a contract for four more Diagnosis Murder books… and the next one is due in March. I have the broad strokes of the story…. but that’s it. The broad strokes. The equivalent of book jacket copy. I’ve still got to come up with the actual story. I’ve been able to procrastinate by doing research on the period… which has given me some plot ideas… but I’ve still got to figure out the murders, the clues, the characters and, oh yes, the story.

This is the hardest part of writing… the sitting around, staring into space, and thinking. This is writing, even if you aren’t physically writing. A lot of non-writers have a hard time understanding this. Yes, just sitting in a chair doing nothing is writing. A crucial part, in fact.

It can be hell… especially when you are on as short a deadline as I am. Everyone has their own method… this is mine:

Once all the thinking is done, I sit down and work out a rough outline… one or two lines on each “scene,” with the vital clues or story points in bold. It’s what I call “a living outline,” because it changes as I write the book, staying a few chapters ahead of me (and, sometimes, requiring me to go back and revise earlier chapters to jibe with the new changes I’ve made… like characters who were supposed to die in the story but don’t). I keep revising the outline right up to the end of the novel. I finish both the book and the living outline almost simultaneously.

While I’m still thinking, and while I’m outlining, and while I’m writing, I compile and maintain what I call “My Murder Book,” a thick binder that contains my outline, my working manuscript, and notes, emails, articles, clips, photographs, post-its…anything and everything relating to my story. By the time the book is done, the binder is bulging with stuff… including my notes on what my next book might be.

Now I’m in the thinking stage, which is why I have time to write this essay. What a great way to procrastinate!

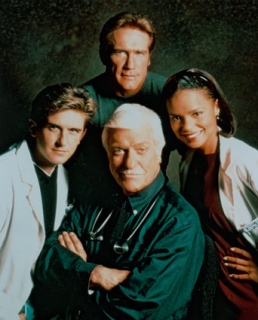

In every Diagnosis Murder book, Dr. Mark Sloan is able to unravel a puzzling murder by using clever deductions and good medicine to unmask the killer.

I wish I could say that he’s able to do that because of my astonishing knowledge of medicine, but it’s not.

I’m just a writer.

I know as much about being a doctor as I do about being a private eye, a lifeguard, a submarine Captain, or a werewolf… and I’ve written and produced TV shows about all of them, too.

What I do is tell stories. And what I don’t know, I usually make up…or call an expert to tell me.

Writing mysteries is, by far, the hardest writing I’ve had to do in television. Writing a medical mystery is even harder. On most TV shows, you can just tell a good story. With mysteries, a good story isn’t enough; you also need a challenging puzzle. It’s twice as much work for the same money.

I always begin developing a book the same way – I come up with an “arena,” the world in which our story will take place. A UFO convention. Murder in a police precinct. A rivalry between mother and daughter for the love of a man. Once I have the arena, I think about the characters. Who are the people the story will be about? What makes them interesting? What goals do they have, and how do they conflict with the other characters?

And then I ask myself the big questions – who gets murdered, how is he or she killed, and why? How Dr. Mark Sloan solves that murder depends on whether I’m are writing an open or closed mystery.

Whether the murder is “open,” meaning the reader knows whodunit from the start, or whether it is “closed,” meaning I find out who the killer is the same time that the hero does, is dictated by the series concept. Columbo mysteries are always open, Murder She Wrote was always closed, and Diagnosis Murder mixes both. An open mystery works when both the murderer, and the reader, think the perfect crime has been committed. The pleasure is watching the detective unravel the crime, and find the flaws you didn’t see. A closed mystery works when the murder seems impossible to solve, and the clues that are found don’t seem to point to any one person, but the hero sees the connection you don’t and unmasks the killer with it.

In plotting the book, the actual murder is the last thing I explore, once I’ve settled on the arena and devised some interesting characters. Once I figure out who to kill and how, then I start asking myself what the killer did wrong. I need a number of clues, some red-herrings that point to other suspects, and clues which point to our murderer. The hardest clue is the finish clue, or as we call it, the “ah-ha!,” the little shred of evidence that allows the hero to solve the crime – but still (hopefully) leaves the reader in the dark.

The finish clue is the hardest part of writing a Diagnosis Murder book – because it has to be something obscure enough that it won’t make it obvious who the killer is to everybody, but definitive enough that the reader will be satisfied when Mark Sloan nails the murderer with it.

A Diagnosis Murder book is a manipulation of information, a game that’s played on the reader. Once I have the rigid frame of the puzzle, I have to hide the puzzle so the reader isn’t aware they are being manipulated. It’s less about concealment than it is about distraction. If I do it right, the reader is so caught up in the conflict and drama of the story, they aren’t aware that they are being constantly misdirected.

The difficulty, the sheer, agonizing torture, of writing Diagnosis Murder is telling a good story while, at the same time, constructing a challenging puzzle. To me, the story is more important than the puzzle — the book should be driven by character conflict, not my need to reveal clues. The revelations should come naturally out of character, because people read books to see interesting people in interesting situations…not to solve puzzles. A mystery, without the character and story, isn’t very entertaining.

In my experience, the best “ah-ha!” clues come from character, not from mere forensics – for instance, I discover Aunt Mildred is the murderer because she’s such a clean freak, she couldn’t resist doing the dishes after killing her nephew.

In my experience, the best “ah-ha!” clues come from character, not from mere forensics – for instance, I discover Aunt Mildred is the murderer because she’s such a clean freak, she couldn’t resist doing the dishes after killing her nephew.

But this is a book series about a doctor who solves crimes. Medicine has to be as important as character-based clues. So I try to mix them together. The medical clue comes out of character.

So how do I come up with that clever bit of medicine?

First, I decide what function or purpose the medical clue has to serve, and how it is linked to our killer, then I make a call to Dr. D.P. Lyle, author of Forensics for Dummies, to help me find us the right malady, drug, or condition that fits our story needs. If he doesn’t know the answer, I go to the source. If it’s a question about infectious diseases, for instance, I might call the Centers for Disease Control. If it’s a forensic question, I might call the medical examiner. If it’s a drug question, I’ll call a pharmaceutical company. It all depends on the story. And more often than not, whoever I find is glad to answer my questions.

The reader enjoys the game as long as you play fair…as long as they feel they had the chance to solve the mystery, too. Even if they do solve it ahead of your detective, if it was a difficult and challenging mystery, they feel smart and don’t feel cheated. They are satisfied, even if they aren’t surprised.

If Dr. Sloan catches the killer because of some arcane medical fact you’d have to be an expert to catch, then I’ve failed and you won’t watch the show again.

The medical clue has to be clever, but it can’t be so obscure that you don’t have a chance to notice it for yourself, even if you aren’t an M.D. And it has to come out of character, so even if you do miss the clue, it’s consistent with, and arises from, a character’s behavior you can identify.

To play fair, all the clues and discoveries have to be shared with the reader at the same time that the hero finds them. There’s nothing worse than withholding clues from the reader – and the sad thing is, most mysteries do it all the time. The writers do it because playing fair is much, much harder than cheating. If you have the hero get the vital information “off screen,” between chapters, the story is a lot easier to plot. But when Diagnosis Murder book works, when the mystery is tight, and the reader is fairly and honestly fooled, it makes all the hours of painful plotting worthwhile.

That, and the royalty check.

When you sit down to write a mystery novel, there are no limitations on where your characters can go and what they can do. Your detective hero can appear on every single page. He can spend all the time he wants outdoors, even at night, and can talk with as many people as he likes. Those may not seem like amazing creative liberties to you, but to someone who makes most of his living writing for television, they are amazing freedoms.

Before a TV writer even begins to think about his story, he has to consider a number of factors that have nothing to do with telling a good mystery or creating memorable characters.

For one thing, there’s the budget and the shooting schedule. Whatever story you come up with has be shot in X many days for X amount of dollars. In the case of Diagnosis Murder, a show I wrote and produced for several years, it was seven days and $1.2 million dollars. In TV terms, it was a cheap show shot very fast.

For one thing, there’s the budget and the shooting schedule. Whatever story you come up with has be shot in X many days for X amount of dollars. In the case of Diagnosis Murder, a show I wrote and produced for several years, it was seven days and $1.2 million dollars. In TV terms, it was a cheap show shot very fast.

To make that schedule, you are limited to the number of days your characters can be “on location” as opposed to being on the “standing sets,” the regular interiors used in each book. On Diagnosis Murder, it was four days “in” and three days “out.” Within that equation, there are still more limitations – how many new sets can be built, how many locations you can visit and how many scenes can be shot at night.

Depending on the show’s budget, you are also limited to X number of guest stars and X number of smaller “speaking parts” per book. So before you even begin plotting, you know that you can only have, for example, four major characters and three smaller roles (like waiters, secretaries, etc.). Ever wonder why a traditional whodunit on TV is usually a murder and three-to-four suspects? Now you know.

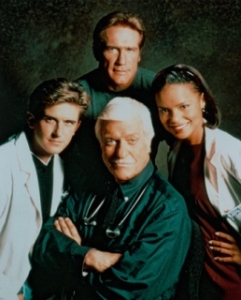

Then there’s the work schedule of your regular cast to consider. On Diagnosis Murder, Dick Van Dyke only worked three consecutive days a week and he wouldn’t visit any location more than thirty miles from his home. Co-star Victoria Rowell split her time with the soap opera Young and the Restless, and often wasn’t available to shoot until after lunch.

On top of all that, your story has to be told in four acts, with a major twist or revelation before each commercial break, and unfold over 44 minutes of airtime.

It’s astonishing, given all those restrictions, that there are so many complex, entertaining, and fun mysteries on television.

Those limitations become so ingrained to a TV writer/producer, that it becomes second-nature. You instinctively know the moment you’re pitched a particular story if it can be told within the budgetary and scheduling framework of your show. It becomes so ingrained, in fact, that it’s almost impossible to let go, even when you have the chance.

I am no longer bound by the creative restrictions of the show. I don’t have to worry about sticking to our “standing sets,” Dick Van Dyke’s work schedule, or the number of places the characters visit. Yet I’m finding it almost impossible to let go. After writing and/or producing 100 episodes of the show, it’s the way I think of a Diagnosis Murder story.

And if you watched the show, it’s the way you think of a Diagnosis Murder story, too –whether you realize it or not. You may not know the reasons why a story is told the way it’s told, but the complex formula behind the storytelling becomes the natural rhythm and feel of the show. When that rhythm changes, it’s jarring.

If you watch your favorite TV series carefully now, and pay close attention to the number of guest stars, scenes that take place on the “regular sets,” and how often scenes take place outdoors at night, and you might be able to get a pretty good idea of the production limitations confronting that show’s writers every week.

And if you read my Diagnosis Murder novels, feel free to put the book down every fifteen minutes or so for a commercial break.

Speaking of which, if there’s actually going to be another Diagnosis Murder novel, I better get back to work… sitting in my chair, doing nothing.

I seem to remember that you wrote one of these and a Monk every six months for a while, or four novels a year. I have no idea how you did that. I can’t call you a literary master, but everything you write is compelling, often funny, and highly literate. I read all of your Monks, but the follow-ons weren’t the same, so I stopped. The Fox/O’Hare ones are engaging enough, and changing before my very eyes, so I will keep up with those too.

Thanks so much for sharing Lee.

Great reading. Especially from someone who’s been there – done that!

I really enjoyed this behind-the-scenes take on writing for tv, and writing mystery books. Thanks for sharing.

Awesome article and I wish I could get this kind of work.

Very much enjoyed the blog, i don’t know how to break this to you gently, but television mysteries no matter how artfully crafted, are very easy for me to analyze, as I have been watching them for more than fifty years, so I much prefer open mysteries, that way it remains entertaining. That is not true with books however, which is why I read much more than watch. When you mentioned character conflict, did you actually mean tension, or if not, to what type of conflict were you referring? One of my all time favorite Natalie/Monk bits occurs when Natalie suggests Monk write a novel…Monk: “Well..what would it be called ? I mean Who would be in it? What would they say? What would the other people say back?”

Keep up the good work…

Thanks, Lee! What an insightful post and now, when I watch Diagnosis Murder, I’ll be thinking of all the things you mentioned.

It’s funny how my tastes have changed. When some of the other mysteries came out years ago, like Columbo and Murder She Wrote, I loved them, couldn’t wait to watch. Now, for some reason, and I’m not saying this because you wrote Diagnosis Murder, but your series is the only one I can stand. On Hallmark Movies & Mysteries, I tried to watch the other two and just couldn’t and can’t give you a good reason why. It could be the characters which I prefer in Diagnosis and the fact that it feels less “dated,” or it could be the scripting. I’m just not sure. I had no idea you wrote Monk, too. What a character!

You’ve provided a lot of entertainment and joy. Thanks for sharing the rest of the story..

A great read for me as I have been writing fo about two years now.

As a budding producer I understand that plane crashes and train wrecks are out the window.

Thanks for the insight!

Here recently, I purchased three more of your DM books through Amazon Marketplace, and finished all three of those; I now have finished 3/4 of your DM book series. Those are some good books there!