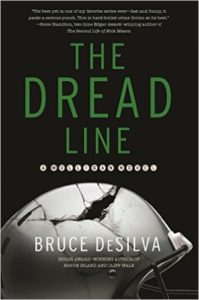

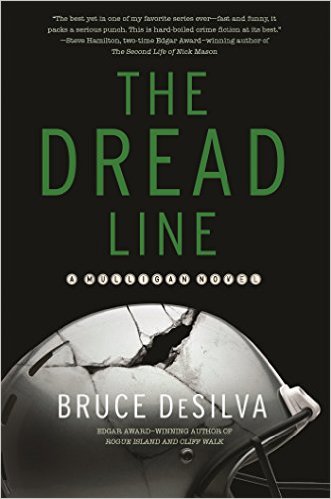

My friend Bruce DeSilva’s The Dread Line, the fifth book in his Edgar award-winning Liam Mulligan series, is coming out in hardcover and digital editions next month and is available for pre-order now. I asked Bruce to share with you the creative struggle he went through writing his new novel.

My friend Bruce DeSilva’s The Dread Line, the fifth book in his Edgar award-winning Liam Mulligan series, is coming out in hardcover and digital editions next month and is available for pre-order now. I asked Bruce to share with you the creative struggle he went through writing his new novel.

An unanticipated disaster struck as I was writing the fourth novel in my series featuring investigative reporter Liam Mulligan: The failing Providence, R.I. newspaper he had been working for abruptly fired him, creating a crisis for both of us.

It was a crisis for Mulligan because he considered journalism his calling, like the priesthood but without the sex. He’d always said that he could never be good at anything else—that if he couldn’t be a reporter, he’d end up selling pencils out of a tin cup.

It was a crisis for me because I owed my publisher another Mulligan yarn.

What was Mulligan going to do now? How would he make a living? And more importantly, how could he continue his life’s work of exposing greed and corruption? It was as if Joe Friday had been stripped of his badge, as if Superman had lost his cape, as if Robert B. Parker’s Spenser couldn’t be a private investigator anymore.

As I sat down to write, the first thing Mulligan and I had to do was invent a new life for him.

I’d never planned on Mulligan getting fired. Fact is, I don’t plan anything when I write. I don’t outline. I never think very far ahead. I just set my characters in motion to see what they will do. But looking back on it now, I can see that Mulligan’s firing was inevitable.

When I first made him a newspaper journalist in my debut novel, Rogue Island, I didn’t know that the book would be the first in a series, so I gave no thought to the possibility that I was writing myself into a corner. I made him an investigative reporter in Providence for three reasons.

- I’d been one myself, and they say you should write what you know.

- Reporters can’t get search warrants or drag people in for questioning, which sometimes makes their jobs more challenging than police work. But they also have an advantage because a lot of people who talk to reporters would never spill anything to the cops.

- But the main reason is that I wanted my novel not only to be suspenseful and entertaining but also to address a serious social issue.

American newspapers are circling the drain. Many already have gone belly up, and economic changes triggered by the internet have forced virtually all of them to slash their news staffs. This is a slow-motion disaster for the American democracy, because there is nothing on the horizon to replace newspapers as honest and comprehensive brokers of news and information.

As someone who spent forty years in the news business, I’ve always been annoyed that journalists are usually portrayed as vultures in the popular culture. The truth is that most of them are hard-working, low-paid professionals dedicated to digging out the truth in a world full of powerful people who lie as often as the rest of us breathe.

It was my hope that as readers followed the skill and relentlessness with which Mulligan worked, they would gain a greater appreciation for what is being lost as newspapers fade away. I made that first novel both a compelling yarn and a lyrical epitaph for the business that Mulligan and I both love.

But as the first novel led to a second, and then several more, the financial health of Mulligan’s employer, the fictional Providence Dispatch, became increasingly desperate. Circulation shrunk, advertising dried up, and hordes of Mulligan’s newsroom colleagues got bought out or laid off.

Fiction followed fact as the once-great Providence Journal, on which The Dispatch was loosely based, also spiraled downward. The newspaper had 340 newsroom employees when I worked there in the early 1980s. It has only 37 reporters and columnists now, and another buyout has just been announced by the chain that bought it a few years back.

As I was completing my fourth novel, A Scourge of Vipers, it became evident that Mulligan’s newspaper career, too, was coming to an end. The Dispatch had been sold off to a predatory conglomerate that had no interest in investigative stories and saw news as something to fill the spaces between the ads. Forced to spend most of his working hours on the routine tasks of putting out a daily newspaper, Mulligan ended up doing most of his investigative reporting on his own time. And his increasingly heated squabbles with his editors were making life untenable for both of them.

By the time that novel ended, Mulligan had been fired in spectacular fashion, accused of a journalism ethics violation that he had not committed. So as I began The Dread Line, the new novel in the series, Mulligan and I sat down together and looked back over his life, considering whether it offered him any hope for the future. There, we discovered a handful of possibilities.

Edward Mason, his young colleague at the paper, was leaving to start a local news website and invited Mulligan to join him. But the new business wasn’t making any money yet, so Mason could only offer starvation wages. Mulligan’s pal Bruce McCracken ran a private detective agency, so perhaps Mulligan could do some work for him. And Mulligan’s mobbed-up friend Dominic Zerilli was retiring to Florida and needed somebody to run his bookmaking business.

What should Mulligan do? Why not all three?

The opening of The Dread Line finds him no longer living in his squalid apartment in a run-down Providence triple-decker. Instead, he’s keeping house in a five-room, water-front cottage on Conanicut Island at the entrance to Narragansett Bay. He’s getting some part-time work from McCracken, although it rarely pays enough to cover his bills. He’s picking up beer and cigar money freelancing for the news website. And he’s running the bookmaking business with help from his thuggish pal, a former strip-club bouncer named Joseph DeLucca.

For the first time in his life, Mulligan has a little money in his pocket at the end of the month. After twenty years as a newspaper reporter, he says it feels strange to be living above the poverty line—and even stranger to be a lawbreaker. But as Mulligan and I see it, he’s not breaking any important ones.

And of course, he still manages to find trouble when it isn’t finding him.

He’s feuding with a feral tomcat that keeps leaving its kills on his porch. He’s obsessed with a baffling jewelry heist. And he’s enraged that someone on the island is torturing animals. All of this keeps distracting him from a big case that needs his attention.

The New England Patriots, still shaken by a series of murder charges against one of their star players (true story) have hired Mulligan and McCracken (not a true story) to investigate the background of a college star they are thinking of drafting. The player appears to be a choirboy, so at first, the job seems routine. But as soon as they start asking questions, they get push-back.

The player has something to hide, and someone is willing to kill to make sure it remains secret.

Mulligan may not be an investigative reporter anymore, but he and I are still in the crime-busting business.

My friend W.L. Ripley is the author of two critically-acclaimed series of crime novels — four books featuring ex-professional football player Wyatt Storme and four books about ex-Secret Service agent Cole Springer. His latest novel is

My friend W.L. Ripley is the author of two critically-acclaimed series of crime novels — four books featuring ex-professional football player Wyatt Storme and four books about ex-Secret Service agent Cole Springer. His latest novel is

My friend author Gerald Duff shares the story behind the writing of his tasty new novel

My friend author Gerald Duff shares the story behind the writing of his tasty new novel

I think it was Heywood Hale Broun who said, “When a professional man is doing the best work of his life, he will be reading only detective novels,” or words similar. I hope, even at my age, I have my best work ahead of me, but when I was writing

I think it was Heywood Hale Broun who said, “When a professional man is doing the best work of his life, he will be reading only detective novels,” or words similar. I hope, even at my age, I have my best work ahead of me, but when I was writing

My friend and

My friend and

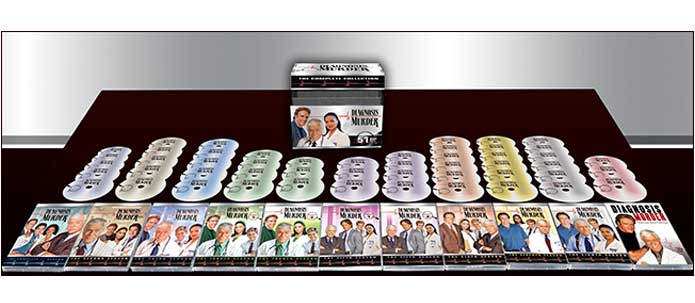

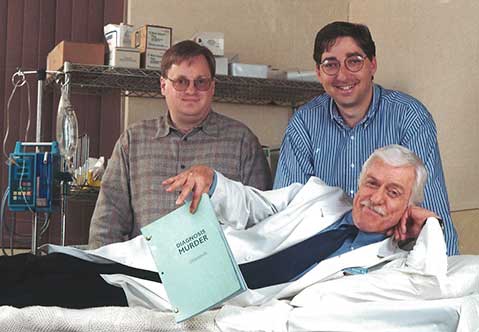

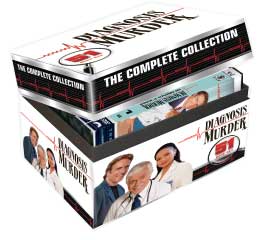

Lee was the executive producer and principle writer of the Diagnosis Murder series, which made our adventure into medical crime drama even more exciting. We knew the writer/producer personally. We don’t usually have that kind of connection to the shows we watch. So what’s Diagnosis Murder about?

Lee was the executive producer and principle writer of the Diagnosis Murder series, which made our adventure into medical crime drama even more exciting. We knew the writer/producer personally. We don’t usually have that kind of connection to the shows we watch. So what’s Diagnosis Murder about?  Watch the first few Diagnosis Murder episodes in a row and you’ll be hooked. It’s so popular there’s even a roaring trade in Diagnosis Murder fanfiction, some of it uncomfortably X-rated. There are literally hundreds of guest stars listed on the show’s Wikipedia page. And the stars of the show, including Dick Van Dyke, Barry Van Dyke, Victoria Rowell and Scott Baio of Happy Days fame, are developed beautifully throughout the series. The plots are satisfyingly twisty and turny, the science bits are fascinating and the stories don’t date. All the hallmarks of top quality crime fiction entertainment, and great fun.

Watch the first few Diagnosis Murder episodes in a row and you’ll be hooked. It’s so popular there’s even a roaring trade in Diagnosis Murder fanfiction, some of it uncomfortably X-rated. There are literally hundreds of guest stars listed on the show’s Wikipedia page. And the stars of the show, including Dick Van Dyke, Barry Van Dyke, Victoria Rowell and Scott Baio of Happy Days fame, are developed beautifully throughout the series. The plots are satisfyingly twisty and turny, the science bits are fascinating and the stories don’t date. All the hallmarks of top quality crime fiction entertainment, and great fun.