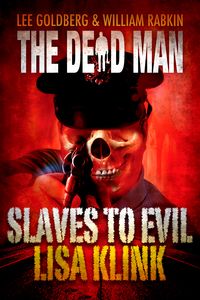

Today marks the debut of Lisa Klink's THE DEAD MAN #11: SLAVES TO EVIL, her first published novel. She's also the first woman (so far) to contribute to the series, which is published more-or-less monthly by Amazon's 47North imprint. Here's the plot…

Today marks the debut of Lisa Klink's THE DEAD MAN #11: SLAVES TO EVIL, her first published novel. She's also the first woman (so far) to contribute to the series, which is published more-or-less monthly by Amazon's 47North imprint. Here's the plot…

Matt Cahill has an unusual gift: he can see the corruption in people’s souls, making the afflicted appear as walking corpses to his eyes. This macabre ability has set him on a one-man crusade to eradicate these servants of an ancient and powerful evil, embodied by the aptly named “Mr. Dark.”

On his way through the small town of Breckenridge, Minnesota, Matt sees the unmistakable signs of corruption in the chief of police and numerous cops. The evil that has consumed them now terrorizes innocents and allows drug and sex trafficking to run rampant. Just as Matt confronts the enslaved cops, a gun-toting teen appears, looking to make Matt pay for murdering her brother. Of course, Matt did kill her brother—he was another corrupted soul who’d been planning a bombing. But how can Matt convince Elena of the truth without any proof?

Trapped between Mr. Dark’s forces and a girl hell-bent on revenge, Matt faces an impossible choice: remove Elena—permanently—or let her kill him and doom the town.

Sounds great, doesn't it? Lisa has spent years toiling in the trenches of primetime television, as a writer/producers on shows like Star Trek Voyager and Missing…and has even written a Las Vegas strip tourist attraction (The Star Trek Experience, which was at the Hilton for years) . So I thought I'd invite her over here for a chat about her career and her creative process.

How did you become a writer?

I’ve written stories ever since I knew how to write. I wrote a play in college and graduated with an English major. After college, I moved to L.A. to work in Hollywood. At first, I wanted to write movies. Then I tried writing a TV spec script and found I liked that better. I took a UCLA Extension class in TV writing from Bill Rabkin, which I really enjoyed. I had been pitching stories to the Star Trek series “Deep Space Nine” and “Voyager,” and finally sold one to DS9. That was my first produced episode. It led to a staff job on “Voyager.”

What do you enjoy most about being a writer?

I love the feeling when I get a moment of action or line of dialogue just right. It’s like thinking of exactly the right comeback to an argument (usually in the car on the way home). For a few minutes, I feel like a genius. Then it’s back to work. I also like the problem-solving aspect of writing, figuring out the right order for the scenes and which clues to drop where.

What drew you to "The Dead Man?"

I was lucky enough to work with Lee and Bill on two TV series, “Martial Law” and “Missing.” We became friends. I heard about the “Dead Man” series they were working on and told them it sounded like fun. So they asked if I’d like to write one of the books. I jumped at the chance. I was right – it has been fun.

You've written scores of produced screenplays, but this was your first, published book. Did you find the transition to prose tricky?

Yes, it was tricky. TV writing is very sparse and functional. A script isn’t a final product in itself, but a blueprint for an episode. If something won’t be on screen, it doesn’t go in the script. With this book, I had to push myself to include more description, emotion and inner thoughts of the characters. There would be no set design or actors to add those elements later.

You've spent many years writing and producing TV series, some of them with Lee Goldberg & William Rabkin. How was writing "Slaves to Evil" different than writing an episode of a TV series? In what ways was it the same?

I found it challenging to write prose after years of scripts. The biggest advantage of a book over TV is the complete lack of budget and network restrictions. I could have as many sets and characters as I wanted. I could use bad words and nasty violence with no censor to stop me. That was fun.

This experience was like TV writing because the premise and main characters had already been established. I had always found the idea of writing a novel intimidating because I’d have to create the whole universe from scratch. This was the perfect transitional step. Also, I was already comfortable working with Lee and Bill, so I knew I had good support.

You've written TV shows, comics, books….you even scripted the "Borg Invasion 4-D" attraction that ran for years at the Hilton in Las Vegas. They are such different mediums. How do you do it? Do you have one guiding philosophy or approach to the writing that you do? What sort of writing do you like best?

I honestly don’t think I have a preference. I’m most comfortable with television, but I really enjoy the challenge of working in different media. Whatever the format, good writing always comes down to story and character. I have to get those right first. Then it’s a matter of shaping the script to fit the final product.

Now that you've written a book, are you tempted to write another outside of "The Dead Man" universe?

I would love to write more books. I read a lot of nonfiction, so I’d like to try that next. I also have a couple of ideas brewing for original novels. I’ll always keep writing, in as many different media as I can. New experiences and new challenges keep it interesting.

![IMG_1121[1] IMG_1121[1]](https://leegoldberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/6a00d8341c669c53ef0167648f0033970b-200wi.jpg)

![IMG_1130[1] IMG_1130[1]](https://leegoldberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/6a00d8341c669c53ef0167648f017d970b-200wi.jpg)